Tracing the Trajectory: India’s Transition to Metal-Less Coronary Interventions

Introduction

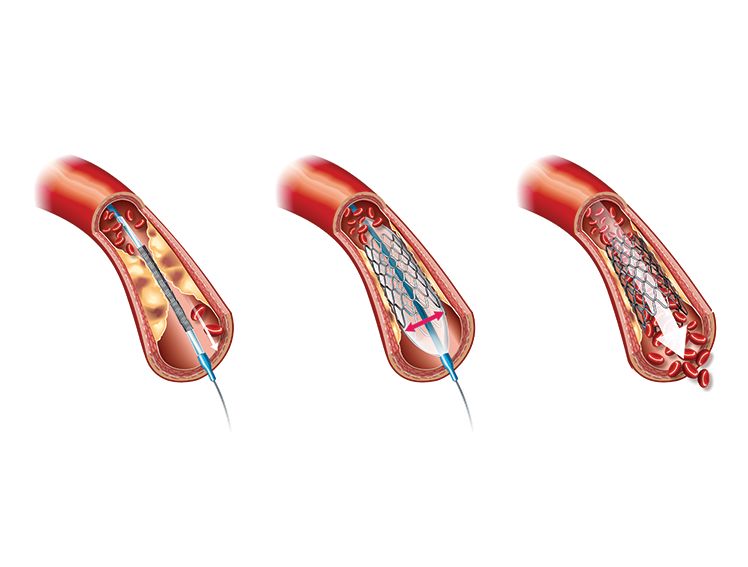

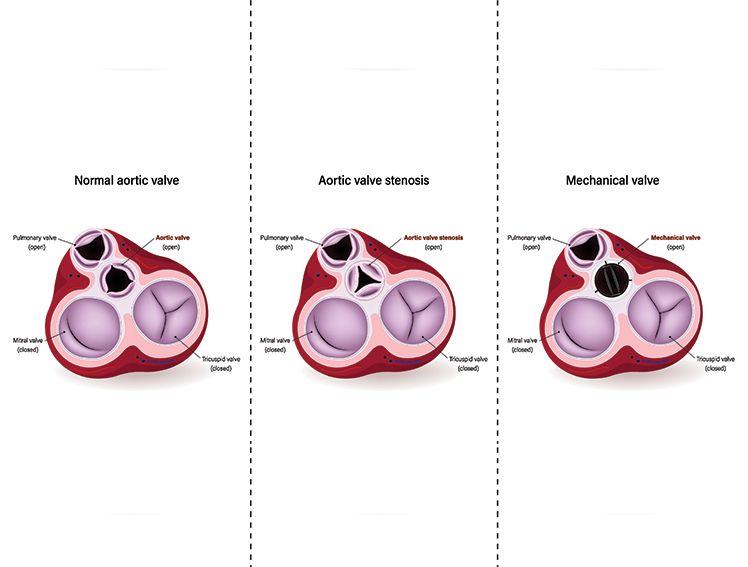

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) also known as Angioplasty is an effective way to treat patients with coronary artery disease. For decades, PCI has employed a variety of stent types. The earliest coronary stents to be adopted widely across the globe were made of metal. Bare metal stents (BMS) have a notable downside, which leads to high failure rates called restenosis1. Restenosis refers to the re-narrowing of the artery following PCI due to inflammation and excessive tissue growth.

The advent of drug-eluting stents (DES) solved the problem of restenosis by incorporating a coating of anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative medications. Although first-generation DES reduced failure rates in PCI and mortality, their reliance on metal stents and permanent polymers introduced novel challenges. Notably, the use of first-generation metal-based DES was associated with blood clots in an artery after PCI, a phenomenon called late stent thrombosis1.

Second-generation DES improved clinical outcomes by using Biocompatible Polymers, and third-generation DES further improved outcomes with Bioabsorbable/Biodegradable Polymer and thin strut stent technology. Each subsequent generation of DES represents marked improvements in biocompatibility and clinical outcomes. However, these stents were also designed to stay permanently which poses challenges in future interventions in the artery in which they were deployed.

Enter metal-less stents

Metal-less stents, also known as BioResorbable Vascular Scaffolds (BVS) or BioResorbable Scaffolds (BRS), are a newer type of stent designed to eliminate the drawbacks associated with BMS and DES. Bioresorbable Scaffolds provide temporary support to a narrowed artery but gradually dissolve over time and become absorbed by the body once they have served their purpose. These stents are typically made from a biodegradable polymer and are capable of releasing anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative drugs. The concept behind BioResorbable stents is to provide temporary scaffolding support without leaving a permanent implant behind.

PCI in India: How BRS changed the landscape

Rates of coronary artery disease are among the highest in India4. In 2015, almost 27% of all medically certified deaths in India were associated with coronary artery disease5. Consequently, the number of percutaneous coronary interventions in India are rapidly rising each year. In 2018, the year-on-year increase in the number of PCI procedures was reported at 13.14%, as per data from the National Interventional Council, the interventional arm of the Cardiological Society of India2. During this year, 98.12% of the stents used for PCI were drug-eluting stents3. In 2008, drug-eluting stents accounted for just over 51% of the total stents used for PCI in India. Therefore, the utilization of drug-eluting stents as a percentage of the total stents employed has nearly doubled over the span of a decade.

Factors underlying choice of coronary stents

The choice of stents used for PCI in India is significantly influenced by market price, which in turn, is now influenced by several measures recently instituted by the Indian government to improve accessibility to advanced stents in the country.

In 2016, India’s Ministry of Health included stents in the National List of Essential Medications. In 2017, India’s National Pharmaceutical and Pricing Authority introduced price ceilings for coronary stents6. Fixed price ceilings for stents have improved the adoption of coronary stent technology in India7. Studies suggest that the use of first-generation DES reduced, and the use of second- and third-generation stents increased in India concurrently with price capping. For example, a single-centre study from Mumbai found that the use of first-generation DES decreased by 41%, and the use of second- and third-generation stents increased by 21% and 20%, respectively, after price ceilings were introduced in 20177.

The adoption of new-generation stents in India will continue to depend on accessibility.

The Role of Meril Life Sciences in Metal-Less PCI

Meril is dedicated to enhancing access to advanced stent technology in India. Recognizing the need for accessible PCI solutions, Meril has developed state-of-the-art medical devices, including affordable next-generation stents that are tailored specifically for Indian clinics.

MeRes100 is a next-generation BioResorbable Scaffold from Meril that offers best-in-class features and improved clinical outcomes in PCI. MeRes100 boasts a 100-micron thin strut, sirolimus-eluting scaffold that gets completely absorbed into the body within two to three years after PCI. MeRes-1 clinical study demonstrated no scaffold thrombosis in patients for a period of up to three years who were treated with MeRes100.

Meril also offers the drug-coated balloon (DCB) MOZEC SEB catheter, which helps clinicians deliver sirolimus using a specialised nanotech drug delivery system to treat in-stent restenosis. The philosophy of these BRS & DCBs is to leave no permanent implant behind and allow the arteries to attain its natural vasomotion.

Furthermore, Meril has an array of advanced balloon dilation catheters tailored for PCI. Among them, the MOZEC PTCA catheter with SC balloon stands out as a superior solution for effectively improving myocardial perfusion. The MOZEC NC PTCA catheter with NC balloon serves as a versatile tool for improving myocardial perfusion and post-delivery expansion of balloon expandable stents. Affordable solutions for PCI from Meril Life Sciences represent a unique mix of innovation and patient-centric approach to healthcare. The endeavors of home-grown companies like Meril will continue to facilitate wider access to life-saving technology, enhancing the standard of care for coronary artery disease in India.

References

Itagaki, B. K. (2012, December 1). Controversies in the use & implementation of drug-eluting stent technology. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3612322/

Arramraju, S. K., Janapati, R. K., Kumar, E., & Mandala, G. R. (2020). National interventional council data for the year 2018-India. Indian Heart Journal, 72(5), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2020.07.018

Ramakrishnan, S., Mishra, S., Chakraborty, R., Chandra, K. S., & Mardikar, H. (2013). The report on the Indian coronary intervention data for the year 2011 – National Interventional Council. Indian Heart Journal, 65(5), 518–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2013.08.009

Kumar, A., & Sinha, N. (2020). Cardiovascular disease in India: A 360 degree overview. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 76(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2019.12.005

Ralapanawa, U., & Sivakanesan, R. (2021). Epidemiology and the Magnitude of Coronary Artery Disease and Acute coronary Syndrome: A Narrative review. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 11(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.201217.001

Wadhera, P., Alexander, T., & Nallamothu, B. K. (2017). India and the coronary stent market. Circulation, 135(20), 1879–1881. https://medicopublication.com/index.php/ijphrd/article/view/19819

A Comparative Study of Coronary Stent Utilization Pattern with respect to Coronary Stent Price Regulation: A hospital-based study from Mumbai, India. (2023). Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development, 14(4). https://medicopublication.com/index.php/ijphrd/article/view/19819